Burying a Year

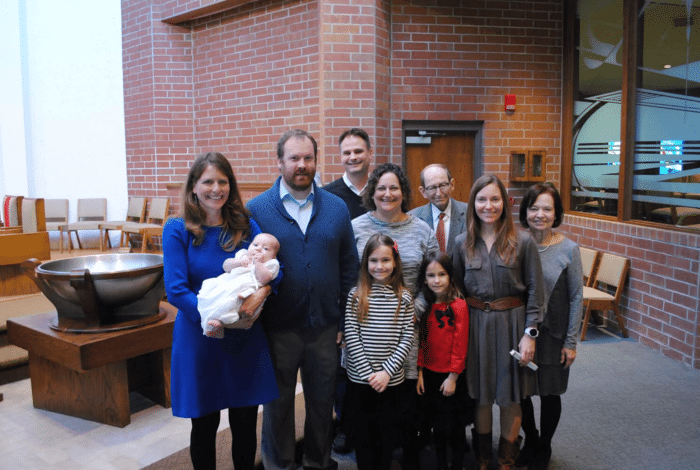

It was Monday evening after Thanksgiving 2017, and I was leaving work later than I wanted, heading to the parking garage in that light gray dusk of pre-winter. I was planning a short trip to the climbing gym, fully reveling in a break from running after a 50-mile race nine days earlier. The race was in Maryland, and Chris and I had spent a few days visiting friends in Bethesda and DC before flying home the day before Thanksgiving. The holiday itself had been wonderful, as it usually is - family, laughter, gratitude, and of course food. That weekend my niece Piper was baptized, and we got some great photos of the whole family. It felt like the Christmas season was suddenly in full swing. My sister Amy had texted me and my other sister Lisa earlier in the day to ask how many strings of lights she could connect end-to-end for the giant tree she and her husband had bought for the first Christmas in their new house. Things were good.

I remember the phone call from my dad clearly now, despite having shoved it deep into the recesses of my brain for many months. “Have you talked to your mom? Amy’s at the hospital. She has bleeding on her brain. She might have to have brain surgery.” The last two words were forced out, like saying them out loud made it too real, or just too terrible. I couldn’t comprehend what I had heard. I had just been texting with Amy hours earlier. Had she been ill and I didn’t know it? Was there an accident? What happened? What was happening? Was this a dream? Was this information somehow wrong? It had to be. This couldn’t be right.

The next couple of hours were a blur. At some point I talked to my mom, talked to Chris and either picked him up at home or met him at the hospital (I don’t remember), and arrived in the lobby of the hospital to convene with my dad and Chris (so did we drive separately? I still don’t remember). And at some point the word aneurysm became part of the conversation (was it in the ER? was it just a theory at first? was it later, at the second hospital?). But there are things about that evening that I wish I could forget, like Amy asking me, “Why is everyone here? Am I dying?” Or the helplessness and fear I felt while driving to the hospital where Amy was being transported via ambulance for neurocritical care. Or my embarrassment about feeling resentful of other patients who were recovering when my sister wasn’t doing as well.

For five days, there were procedures and questions and some answers and more questions. I will spare you the details because many of them are still painful and confusing. There were hours spent in waiting areas. There were lots of tears. There was the endless kindness of friends. There was hope. And then, December 2, there was tragedy. Six days after that, my sister’s casket was lowered into the ground on a frigid day, and it felt like the earth dropped out from beneath me. I was shattered. For weeks I was mostly numb to everything around me. Nothing mattered in that empty void, in a way that made me careless about my own mortality. Anne Lamott sums up that feeling perfectly in this passage from Almost Everything: Notes on Hope:

Love has bridged the high-rises of despair we were about to fall between. Love has been a penlight in the blackest, bleakest nights. Love has been a wild animal, a poultice, a dinghy, a coat. Love is why we have hope.

So why have some of us felt like jumping off tall buildings ever since we can remember, even those of us who do not struggle with clinical depression? Why have we repeatedly imagined turning the wheels of our cars into oncoming trucks?

We just do.

To me, this is very natural. It is hard here.

To love is to feel pain, sometimes a dull thrum of melancholy or nostalgia, and sometimes a wave of sorrow for what will never be the same. Grief is now woven into my life, creating a new texture. I am now a woman who has lost her sister - too young, too soon, too suddenly (as if older, later, or with warning makes grief any easier). I am also, and have always been, a solution-finder. If things don’t go as planned, I get frustrated but then I find an acceptable way to move forward. The past year has thrown a wrench in all my best attempts at fixing things. Some things can’t be fixed, and there is no alternative solution. But grief has also taught me to be kinder to myself and to others, to greet with tenderness whatever feelings are at the surface in the moment. It is a daily commitment of acceptance - the good days and the bad days, the easy days and the hard days. Sometimes the easy stuff feels hard, like chopping vegetables, or parking at the mall; I’ll find myself vaguely absent from the immediate task, and suddenly I’m weeping and I have to stop everything to allow the emotion to wash over me. Sometimes it feels like I should be sad and weepy, but I can’t muster any tears. Those moments are surprisingly heartbreaking in their own way, like I’m betraying my grief or even my sister herself. It’s a confusing feeling, and I’m often left wondering when I’ll figure it out. The answer, of course, is that I won’t. In the song The World Moves On (which is actually about a breakup), Jens Lekman nails it:

You don’t get over a broken heart

You just learn to carry it gracefully

So now I’ve made it through the last of the “first holidays without Amy,” and it feels like a milestone of the worst kind. There will be many other firsts without her, most of which involve her young daughters, and my heart aches the most thinking about them and those future moments. But I’m also learning to avoid projecting my pain onto them. They will experience life in a way I didn’t have to, and I can’t begin to understand what their grief is like or how it will manifest itself throughout their lives. I can only try to be a source of warmth and light for them, as I continue searching for grace and light myself, year after year.

Both mind and earth are made

of what its light gives and uses up.

So joy contains, survives its cost.

The dead abide, as grief knows.

We are what we have lost.

(Wendell Berry, from Elegy)